In the month of October we will be marking Black History Month by sharing a series of short essays written by four recent graduates of the History Department at the University of Manchester. These students were part of Kerry Pimblott’s third year seminar on the Black Freedom Movement and were tasked with putting their new historical skills to work by performing original research on the transnational links between movements for racial justice in the US and UK. We would like to extend our thanks to the many archivists and librarians who assisted the students in developing these important profiles in Black British History.

Our final blog post on Stokely Carmichael’s July 1967 visit to London is from David Shaw, a recent graduate of the University of Manchester History Department.

In July of 1967, Stokely Carmichael, the leader of SNCC and one of the most prominent leaders in the American Black Power Movement, descended upon London as part of an international tour. A speech he made at the Dialects of Liberation Congress during his time in London is widely regarded as a pivotal moment in the birth of the British Black Power movement, however its role as a catalyst has been largely exaggerated and ignores the preceding developments in Black British history.

This article will explore how Carmichael’s brand of Black Power expressed in his speech appealed to Black Britons, consequently inspiring many to support the British Black Power movement. However, whilst acknowledging the grand impact Carmichael’s visit had on the British Black Power movement, this article will ultimately contend that the movement was already well established before Carmichael’s visit.

Race relations in Britain prior to the Congress

The early-mid 1960s delivered little, if any, positive change for blacks in Britain. Between 1961 and 1964, Britain’s black population tripled from about 300,000 to 1 million, however whilst the black population grew in Britain, so too did the intensity and scope of racism. [1] Racism was no longer confined to civilian attacks, such as the Notting Hill Race Riot of 1958, racism in the 1960s became entrenched within the political framework of British society.

Politicians began to use racist rhetoric to win elections; one striking example is the Conservative politician Peter Griffiths who won an election for Parliament in 1964 in Smethick, Birmingham through using the slogan “If you want a nigger neighbour, vote Labour.” Racism was further institutionalised through legislation such as the Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1962, it’s ‘obvious intention’ being to limit the inflow of black people into Britain. [2] By the late 1960s, racism had become “institutionalised, legitimised and nationalised” to a point at which had been unthinkable in 1958. [3]

In conjunction with intensifying racism, the domestic conditions for blacks, such as police brutality and discrimination in housing worsened. Within the British civil rights movement, there was an increase in discourse over how best to combat the institutionalisation of and increase in racism. The group the Campaign Against Racial Discriminaiton (CARD), one of the main organisations within the British movement, disintegrated in 1967 due to disunity in part stemming from black members suspicions of white liberal members who continued to emphasize working within the “machinery of the state to secure racial equality” even after it had been proven to be ineffective.” [4] Blacks, feeling excluded from politicians concerns, clearly did not trust the British state, they realised an ulterior route was needed to achieve uplift. It was under this condition of “deepening crisis” among black British activists over the future of the movement that Stokely Carmichael arrived in London in July of 1967.[5]

The Dialectics of Liberation Congress

Carmichael was in London as part of a world tour to promote his new book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation. Carmichael was invited to talk at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress in July of 1967. The congress was a unique expression of the modern politics of the 1960s, where “key social issues of the next decade” were to be discussed by prominent intellectuals and writers. [6] The congress was composed of notable attendees such as Herbert Marcuse and R.D. Laing, however Stokely Carmichael was by far the most controversial speaker. The conference was emblematic of the counterculture of the 1960s. Angela Davis, who attended the conference, notes in her autobiography that “the floor was covered with sawdust,” that the air “reeked heavily of marijuana”, and that there were rumours one speaker “was high on acid.”[7] It was under this cliche vision of 1960s counterculture that Carmichael unleashed his radical brand of black activism; black power, to a British audience. Carmichael’s vision provided hope and inspiration for blacks whilst simultaneously deeply concerning British politicians and the British press.

Carmichael’s Speech

When Carmichael came to speak at the conference, attendee Erling Eng writing in 1967 describes how there was a turnout audience to see Carmichael, through the use of his powerful oratory skills Carmichael had “the audience in the palm of his hand” [8]

A key point of Carmichael’s speech was the call for blacks to not ignore blackness and become equal, but to demand equality through blackness, to negotiate on their own terms. Carmichael believed that blacks should “respond in our own ways, on our own terms, in a manner which fits our temperaments.” [9] The notion of taking ownership and demanding change was key to black power. Growing discourse within the US Civil Rights Movement involved many shifting their support toward the Black Power Movement due to it’s emphasis on self-determination supporting the self-determining methods employed by leaders in the Black Power movement. Many saw the legal route, by working through the state apparatus as failing, rather blacks felt the need to demand change on their own terms rather than accommodating to the strategies proposed by white liberals who had failed them.

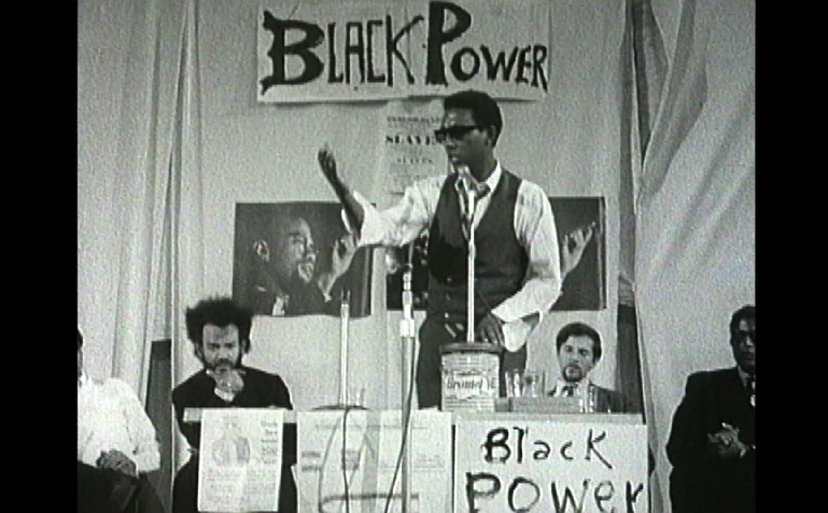

Carmichael’s anger with the failure of the strategy of accomodating to white liberal methods is evident in Figure 1. In a heated debate with a white audience member at the Congress following his speech, Carmichael presses the audience member asking “what have you done to stop it (white violence towards blacks)?”. This anger at the failure of legal methods would have resonated heavily with Black Britons who had become increasingly distrustful of the state and of working with white liberals as evident in the split of CARD. Carmichael’s vision of self-determination and empowerment provided an inspiring alternative to many black Britons

Carmichael also centres his speech around attacking white Western ‘civilisation’, stressing the struggle of the Third World against the oppression of the colonial West. Carmichael emphasises the notion of a global struggle of all black people known as the “Third World.” For the Black Power movement, the struggle for racial equality was a transnational one, it was not simply confined to the U.S. Carmichael explains how Black Power meant that “black people see themselves as a part of a new force, sometimes called the Third World; that we see our struggle as closely related to liberation struggles around the world.” [10]

This transnational collective identity of blacks based on a shared history of being subjugated to colonial rule transformed British blacks from being “an isolated and outnumbered minority to an integral part of a militant global majority.” [11] Carmichael emphatically exclaimed that anytime the white man touches one of the people in the Third World, “he’s going to go to war with all of us.”

Credit: Still from Anatomy of Violence directed by Peter Davis. Available at: https://50.roundhouse.org.uk/content-items/dialectics-liberation-pictures

Carmichael’s emphasis on a global, anti-imperialist struggle appealed with great zeal to many blacks in Britain who had a “tradition of activism” in fighting for independence in the Caribbean and Africa before immigrating to Britain. [12] Carmichael’s roots in Trinidad left him with a great resentment for colonial Britain which transmitted so powerfully in his speech. Carmichael reverberated with black Britons like no American civil rights activist before him, they could relate to his subjugation to the British Empire and therefore supported his arguments more than they had for any black American activist before him.

Carmichael pushes the exploitation of blacks further, alluding to the anti-capitalist element of the Black Power movement. Carmichael argues that “capitalism and racism seem to go hand in hand.” [13] For Carmichael, International white supremacy is driven by the economic exploitation of blacks throughout the Third World.The West had exploited blacks through slave labour and from the mid-twentieth century onwards through cheap labour to build its nationsThrough economic exploitation racism became institutionalised, consequently blacks lack of economic power made it near impossible for them to fight for their rights in an inherently oppressive system.Having been ‘welcomed’ to Britain and exploited as a form of cheap labour, black Britons felt the full force of race based economic exploitation, they essentially became a sub-class. This class-based analysis that underpinned Black Power ideology was“well-suited to the British context,” they could relate to the economic oppression Carmichael was referring to. [14]

The birth of Black Power in Britain?

Carmichaels visit in London unquestionably had an impact on black British politics. Obi Egbuna, the founder of the Universal Coloured People’s Association (UCPA) in 1967 and the British Black Panthers in 1968, saw Carmichael’s visit as a seminal moment in the British Black power movement. Writing in 1971, Egbuna described Carmichael’s visit as being “like manna from heaven” and argued that, ”’It was not until Stokely Carmichael’s historic visit in the Summer of 1967 … that Black Power got a foothold in Britain.” [15]

The impact of Carmichael’s speech was felt immediately. Within a week of his speech the UCPA had expelled its white members and adopted the ideology of black power and Carmichael had been banned from Britain, within a month Michael X, who “quickly became the media face of black power in Britain,” was arrested for inciting racial hatred.[16]

Egbuna’s manifesto for the UCPA distributed in September, 1967, titled Black Power in Britain, drew heavily on Carmichael’s Roundhouse speech. Egbuna’s manifesto affirmed black as beautiful, recognised that blacks were part of a transnational struggle and was critical of capitalism, echoing the points made in Carmichael’s speech.[17]

Furthermore, C.L.R James, a prominent leader in the British Black power movement who attended the Congress, celebrates the impact of Carmichael’s visit. James recalls how Carmichael’s presence and speeches “made the slogan Black Power reverberate” with such energy throughout Britain. [18] Black Britons were clearly inspired by Carmichael’s visit.

However, to claim Carmichael’s speech being responsible for the birth of the British Black Power movement is to deny the importance of developments before his visit. Before Carmichael even came to Britain he was aware that “Black Power formations” had already “begun to emerge”, he came wishing to establish connections with the preexisting movement. [19]

One of those groups was the Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS), which had been founded by Michael X in 1965, two years prior to Carmichael’s visit. The group promoted black empowerment and self-reliance, it even created a sub-body known as the Defence that “provided legal assistance to black people in trouble with the police.” [20] Michael X had been inspired to form RAAS as a result of Malcolm X’s visit to Britain in 1965. For years after his visit, Malcolm X would “provide a constant touchstone for black politics and culture in Britain.”[21] Malcolm X’s autobiography would remain a best-seller in black bookshops in Britain after his visit, his influence caused a spike in the British black power movement before Carmichael’s visit

Other organisations and movements practised black power through celebrating black identity and promoting the belief of the black struggle being a transnational, anti-colonial fight prior to Carmichael’s visit. Claudia Jones, a communist from the Caribbean, and Ashwood Garvey, the widow of Marcus Garvey, ran the West Indian Gazette from 1958-65. The political perspective that Jones and Garvey promoted in the gazette was “internationalist and emphasised the interplay of class and race,” such thinking “foreshadowed the ideology” of British Black Power groups in the late 1960s. [22] Though the work of Jones and Garvey was not categorised as black power, many parallels can be drawn between the ideology that underpinned the Gazette and the ideology that underpinned the British Black Power movement of the 1960s.

The legacy of Carmichael’s visit

Whilst Carmichael’s visit was not responsible for the birth of the British Black Power movement, his visit was still influential in its development. Two of the key leaders of the British Black Power movement, Egbuna and CLR James, were inspired deeply by his speech. Whilst Carmichael’s ideology was not new in Britain, it was his ability as a profound orator and leader that made his visit so impactful and inspired the likes of Egbuna and James. He presented his ideas as if they were at the apex of black modernity, his raw energy and emphasis on grassroots activism made his views seem as if they were new. [23] This star quality of Carmichael brought a lot of attention to the British Black Power movement, helping it develop to new heights. Prior to Carmichael’s visit there had been little media coverage of Black Power in Britain, however there were “daily reports” in newspapers on Carmichael’s activities. Gajo Petrovic, a speaker at the Congress, notes how in these reports the Congress became a mere footnote “incidentally mentioned as a meeting where Carmichael made a speech.” [24] Carmichael’s speech was even debated in Parliament and he was subsequently banned from Britain. The increased awareness and support of the British Black Power movement that arose as a consequence of Carmichael’s visit should not be understated.

The pure energy and inspirational deliverance of the main tenets of Black Power by Carmichael during his visit certainly propelled the British Black Power movement to new heights, inspiring many British Blacks to join the movement. Despite this, the British Black Power Movement predated his visit in 1967. Organisations such as RAAS and the West Indian Gazette were promoting many of the key tenets of Black Power prior to Carmichael’s visit. Carmichael’s visit was by no means responsible for the birth of the British Black Power movement, it is better remembered as a crucial stepping stone forward it. Carmichael’s energetic deliverance of the black power message helped to increase awareness of the British Black Power movement and more importantly inspired many of its future leaders and activists.

References

[1] James Whitfield, Unhappy Dialogue: The Metropolitan Police and Black Londoners in Post-war Britain (London: Willian Publishing, 2004), p.22

[2] Peter Fryer, Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain Book (Pluto Press. 2010) p.382

[3] Fryer, Staying Power, p.381

[4] Rosalind Wild, “‘Black Was the Colour of Our Fight.’ Black Power In Britain, 1955-1976” (unpublished Ph.D, University of Sheffield) p.75

[5] Rob Waters, Becoming black in the Era of Civil Rights and Black Power,’ in Thinking Black: Britain 1964-1985 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019) p.27

[6] David Cooper, The Dialectics of Liberration, (Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd., 1968), back cover.

[7] Angela Davis, An Autobiography (New York: International Publishers, 1988), p.149.

[8] Erling Eng, ‘Beyond Psychiatry?’ The Hudson Review, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Autumn, 1967), 471

[9] Stokely Carmichael quoted in Cooper, The Dialectics of Liberration, p.170

[10] Cooper, The Dialectics of Liberation, p.172

[11] Ashley Dawson, Mongrel Nation: Diasporic Culture and the Making of Postcolonial Britain (University of Michigan Press, 2007) p.50

[12] Anne-Marie Angelo, ‘The Black Panthers in London, 1967–1972: A Diasporic Struggle Navigates the Black Atlantic Anne-Marie Angelo,’ Radical History Review Issue 103 (Winter 2009), 21

[13] Cooper, The Dialectics of Liberation, p.161

[14] Wild, “Black Was the Colour of Our Fight”, p.83

[15] Obi Egbuna, Destroy This Temple: the Voice of Black Power In Britain (London, 197 1), p

p. 15,

[16] Paul Field, ‘Obi B. Egbuna, C. L. R. James and the Birth of Black Power in Britain: Black Radicalism in Britain 1967–72,’ Twentieth Century British History, Volume 22, Issue 3, (2011), 392

[17] Field, ‘Obi B. Egbuna’, 396

[18] C. L. R. James, ‘Black Power’, in Anna Grimshaw, ed., The CLR James Reader (Oxford, 1992), p. 362

[19]Stokely Carmichael with E. M. Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: the Life Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (New York: Scribner 2003) p. 572

[20] James Whitefield, Unhappy Dialogue: the Metropolitan Police and black Londoners in post-war Britain, (London: Willian Publishing, 2004) p.65

[21] Waters, Thinking Black: Britain 1964-1985, p.25

[22] Wild, “Black Was the Colour of Our Fight”, p.33

[23] Waters, Thinking Black: Britain 1964-1985, p.30

[24] Gajo Petrovi, “The Dialectics of Liberation,” Praxis: Revue Philosophique 4 (1967): 610

3 Comments Add yours