In the month of October we will be marking Black History Month by sharing a series of short essays written by four recent graduates of the History Department at the University of Manchester. These students were part of Kerry Pimblott’s third year seminar on the Black Freedom Movement and were tasked with putting their new historical skills to work by performing original research on the transnational links between movements for racial justice in the US and UK. We would like to extend our thanks to the many archivists and librarians who assisted the students in developing these important profiles in Black British History.

Our first blog post on protests following the death of 21-year-old Colin Roach in 1983 is from Tom Ramsden, a recent graduate of the University of Manchester History Department.

“Who killed Colin Roach? A lot of people want

to know,

Who killed Colin Roach? Them better tell the

people now,

What we seek is the truth, youth must now

defend the youth,

Who killed Colin Roach? Tell the people now.”

— Benjamin Zephaniah, ‘Murder’, 1983.

On the 12th of January, 1983, Colin Roach, a 21-year-old Black British man, died from a shotgun wound to the mouth inside Stoke Newington police station.1 The next day, after Scotland Yard had issued a press release declaring that Roach had committed suicide, a group of family, friends, and other locals protested outside Stoke Newington police station, demanding to be told the truth about the suspicious circumstances surrounding the young man’s death.2 The poet Benjamin Zephaniah attended the first protest, and his poem, ‘Murder’, incorporated a chant shouted by the crowd: ‘Who killed Colin Roach? The people want to know’.3 This article will explore the ways in which Hackney residents responded to racist violence against Black youth, especially following the deaths in police custody of Michael Ferreira in 1978 and Colin Roach in 1983. Following both of these tragic events, community members organized protests which combined public acts of mourning with calls for explanations from the police, in order to condemn the police’s negligent, violent, and racist attitude towards Black lives. Both movements challenged the official police and media narratives of how the young men had died in custody, using alternative, community-controlled forms of media to communicate the injustice of the police’s treatment of the young men, as well as the community’s grief at their loss. These poems, plays, and photographs connected the movements to an international tradition of protest against racial violence and injustice, and made them accessible across spatial and temporal boundaries. Not only did the deaths of Ferreira and Roach, and the Hackney community’s response to them, reflect historic movements against racial violence and systemic racism in America and Britain, but they also resonate with the international Black Lives Matter movement today, serving as a reminder of the power of community action and media representation in the ongoing struggle against racism.

The Murder of Emmett Till and the Politics of Mourning

I will frame my discussion with an analysis of the international politics of mourning Black bodies, and the use of alternative media narratives and public funerals as tools of protest. The murder of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old Black boy from Chicago who was brutally lynched by several white men in 1955 while visiting relatives in Mississippi, is considered by historians to be one of the catalytic moments of the Civil Rights Movement in America, galvanizing a generation of activists known as the ‘Emmett Till Generation’.4 Adolescents when Till was murdered, this generation would become the key organizers, speakers, and participants in the central period of the Civil Rights Movements in the 1960s and 1970s. The political resonance of Till’s murder was largely due to the large-scale media coverage of the tragedy and the subsequent trial, as well as the politicization of the mourning of his body.5 Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, decided to leave the casket open at her son’s funeral, which an estimated 600,000 people attended, in order for ‘the world to see what I had seen’, and an image of Till’s tortured face was publicized by the popular African American run Jet magazine and newspaper the Chicago Defender.6 Former Detroit congressman Charles Diggs described the picture in Jet as ‘the greatest media product in the last forty or fifty years, because that picture stimulated a lot of interest and anger on the part of blacks all over the country’.7 The trial of two men involved in the murder in Tallahatchie County also received widespread media coverage, which threatened to cast ‘the entire nation in a negative light’, and the not guilty verdict ignited ‘monster rallies’ in cities across America.8 The public funeral and protests following the verdict sought to counter the injustice of the trial by emphasizing the collective grief and outrage felt across the nation. This highlighted the injustice of the system of entrenched white supremacy which enabled Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, who later confessed to their complicity in the murder, to walk free.9 In this way, the mourning of Emmett Till became a political act: the widespread images of his brutalized face exposed the hypocrisy of those who would defend, condone, or conceal racial violence, while the massive public outpouring of grief across America demonstrated that such violence would not be tolerated without resistance.

The racism experienced by Black British communities took a different form to that experienced by African Americans. For the majority of Black Britons in the 1950s the experience of racism was shaped by hostile white reactions to postwar migration.10 Many people of African or Caribbean descent who exercised their rights as Commonwealth citizens by moving to Britain ‘encountered violence, racism, exclusion, and an evolving “Keep Britain White” mentality that attempted to bar them from full inclusion in British society’.11 As Kennetta Hammond Perry has highlighted, although in Britain ‘the official institutions of Jim Crow did not reside in plain view’, Black Britons experienced ‘some of the accoutrements characteristic of Jim Crow’ through racial discrimination in employment, welfare, and housing.12 Furthermore, the explicit racism of the violence in Nottingham and London in 1958 called into question Black Britons’ rights as citizens to feel a sense of belonging and security.13

“Who Killed Michael Ferreira?”

This systemic, insidious racism in Britain made itself particularly apparent through the treatment of Black communities by the police. In Hackney, Stoke Newington police force had a notorious reputation for its overheavy, violent, and frequently deadly interactions with Black residents.14 The death of Aseta Simms in custody in 1970 led to a headline in Black Voice, the paper of the local Black Unity and Freedom Party, demanding to uncover ‘Who killed Asetta Simms?’.15 This demand for accountability from the police force became a rallying cry, reproduced again and again as Hackney residents protested against police disregard for Black lives. In 1978, Michael Ferreira, a nineteen-year-old Guyanese-born Hackney resident, died inside Stoke Newington police station while seeking medical assistance after being stabbed by a gang of white youths, who were reportedly affiliated with the National Front, a British white supremacist group.16 Shocked by the police’s negligence, who held Ferreira for questioning and did not call an ambulance until it was too late, a procession of hundreds of mourners marched to the steps of Stoke Newington police station.17 Alan Denney, a Stoke Newington resident, participated in the march and took photographs of the procession (which are available to view here).18 The photographs show a multi-racial group marching up Stoke Newington high street behind a hearse containing Ferreira’s body, without signs or banners but with some fists raised in the recognisable salute of the Black Power movement, a symbol of defiance and strength of the Black community. I spoke to Alan about his memories of that day. He described the atmosphere of the march as a ‘somber occasion’, with a ‘simmering sense of anger and disbelief’.19 People were handing out leaflets, and the march encountered a large group of police when it arrived at Stoke Newington police station, where the procession stopped before family and friends went on to a more private funeral service.20 Alan commented that this march was characterised by the outrage and grief of the community, expressed in shocked, reflective silence, which contrasted with the more politically volatile demonstrations a few years later following the death of Colin Roach, which explicitly criticised the police with banners and chants.21

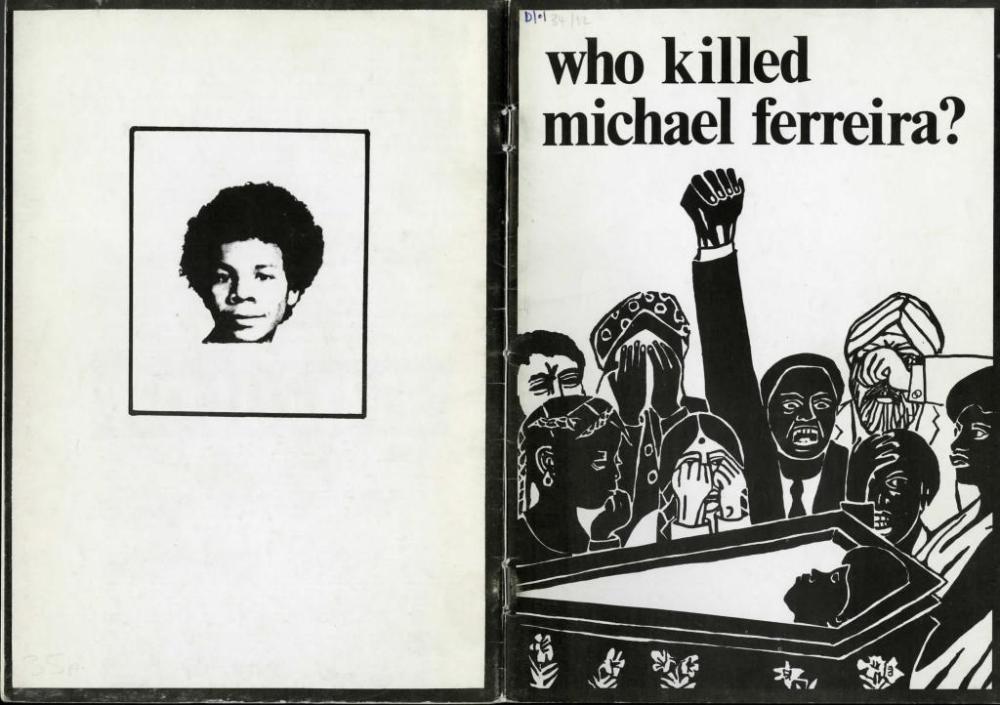

Nevertheless, Ferreira’s death represented a significant demonstration of the popular discontent with policing in Stoke Newington, and had a lasting impact on Hackney residents, especially young people. In 1979, an anonymous group of secondary school students wrote a play, published in a pamphlet entitled ‘who killed michael ferreira?’, which portrays the community attitude towards his death.22 In the play, the events of the night of December 10th, 1978, are imagined by students who did not know Ferreira, but were clearly affected by his death. They present his encounter with a gang of hyperbolically racist white youths, who harrass and insult Ferreira before stabbing him.23 They narrate the decision of Ferreira’s friends to take him to the police station for help, who reluctantly agree, aware that ‘[o]nce we’re in there we’ll never get out’.24 Confirming the Black boys’ fictional, yet tragically accurate, fears, the police harass Michael and his friends, accusing them of ‘starting trouble’, and instead of calling an ambulance interrogate Ferreira and his friends, racially profiling them and refusing to believe their version of events.25

The content of this play highlights the significance of Michael Ferreira’s death to the community of Hackney as a symbol of the police’s racist hostility. Furthermore, the pamphlet ends with a newspaper extract describing the reaction of Ferreira’s mother, Mrs. Ann Moses, to the sentencing of her son’s killer for only 5 years. ‘There is no justice in this land for Black people’, Mrs. Moses remarks, after an all-white jury passed the verdict, which was met by cheers from National Front supporters who had filled the courtroom.26 In order to counter the failure of official justice, the sympathetic community of Hackney took matters into their own hands, taking to the streets to signify both their grief and their anger at the injustice done to Ferreira and his family. The demonstration of popular opposition to policing was particularly significant in the late 1970s and 1980s, as the Metropolitan Police Commissioner at the time, Kenneth Newman, epitomized the belief in policing-by-consensus by remarking that ‘a society that felt well policed was well policed’.27 By expressing their feelings of being badly policed, Hackney residents thus demonstrated the reality that they were being badly policed.

“Who Killed Colin Roach?!”

Following the death of Colin Roach, the protests against Stoke Newington police force were much more politically explicit, with chants accusing the police of murder and placards depicting Colin Roach’s face, framed by the demand for a public inquiry.28 An organization was formed, the Roach Family Support Committee (RFSC), which directed the public’s anger into a clear demand for an independent inquiry into the circumstances surrounding Roach’s death, in order to get justice for the Roach family.29 The demonstrations continued throughout 1983 and the ensuing decade, culminating in 1988 when the RFSC held an independent inquiry into Roach’s death, and published a 313 page study of Policing in Hackney, which connected the Roach case to Ferreira’s and other historic examples of police racism and violence in Hackney since 1945.30

Benjamin Zephaniah’s poem about Colin Roach, ‘Murder’, which drew directly from the chants of protestors, exemplifies the function of the protests to challenge the branding of Roach’s death as ‘suicide’ by police and affiliated media.31 For Zephaniah, the protests connected Colin Roach to ‘all the other cases of racial injustice taking place at the time’, and there was a ‘tangible feeling of: ‘Who is next? It could happen to me’’.32 To this end, Zephaniah intended to write a poem that ‘people could chant on a demo’, and that could have a powerful impact by being performed around the country, as ‘[t]here was very little in the way of coverage in mainstream media and it was left to the poets and musicians to tell the story up and down the country. I would be in Birmingham and explain I was at a police station, and to get the emotion right I’d have to go back to the emotion of that day’.33 In this way, alternative forms of media, such as poetry, plays, and photographs, were vital in not only recording the movements for future generations, but also for transporting their energy across geographical boundaries, enabling the connection of otherwise localized issues into larger campaigns against policing and racial discrimination in Britain.

Without the photographs, poetry, and plays that captured the movements against racist injustice in Hackney in the 1970s and 1980s, there would be little trace of these historic, community-driven protests. In a similar fashion to the response to the funeral and photos of Emmett Till, these movements in Hackney expressed the community’s grief, visibly and publicly challenging the official narratives which obscured the unjust and violent persecution of Ferreira, Roach, and other Black lives. These cultural artefacts have allowed the issues and activities of the protests to be re-examined today, where they resonate with the ongoing struggles against racial discrimination and police brutality in the international Black Lives Matter movement. The Black Lives Matter movement has taken the use of alternative forms of media for political activism to new heights, utilizing the international connectivity and visibility of online video sharing and social media platforms to expose and protest against narratives which justify and perpetuate police violence against Black people, galvanizing individuals across the world to participate in ongoing struggles for justice and equality.

Foonotes:

- Rosa Schling, The Lime Green Mystery: An Oral History of the Centerprise Co-operative (London: On the Record, 2017), p. 46.

- Institute of Race Relations, Policing Against Black People (London: Institute of Race Relations, 1987), pp. 50-51; John Eden, ‘“They Hate Us, We Hate Them”: Resisting Police Corruption and Violence in the 1980s and 1990s’, Datacide, 14(2014), page number n/a <https://datacide-magazine.com/they-hate-us-we-hate-them-resisting-police-corruption-and-violence-in-hackney-in-the-1980s-and-1990s/> [accessed 12.05.2021].

- Emma Bartholomew, ‘Benjamin Zephaniah on how Colin Roach’s death inside Stoke Newington Police Station sparked a movement 35 years ago’, Hackney Gazette (2018) <https://www.hackneygazette.co.uk/news/benjamin-zephaniah-on-how-colin-roach-s-death-inside-stoke-3585066> [accessed 12.05.2021]. To listen to the poem in full see ‘Benjamin Zephaniah: Who Killed Colin Roach?’, youtube.com (2014) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=njs3I4ECIe0> [accessed 12.05.2021].

- Frederick C. Harris, ‘It Takes a Tragedy to Arouse Them: Collective Memory and Collective Action during the Civil Rights Movement’, Social Movement Studies, 5:1 (2006), p. 26, p. 35.

- Shawn Michelle Smith, ‘The Afterimages of Emmett Till’, American Art, 29:1 (2015), pp. 23-25.

- Henry Hampton et al., Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement From the 1950s Through the 1980s (New York: Bantam Books, 1990), p. 6; Smith (2015), p. 22; Harris (2006), pp. 37-38.

- Harris (2006), p. 38.

- Darryl Mace, In Remembrance of Emmett Till: Regional Stories and Media Responses to the Black Freedom Struggle (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2014), p. 135; Harris (2006), p. 34.

- Mace (2014), p. 137.

- Kennetta Hammond Perry, ‘“Little Rock” in Britain: Jim Crow’s Transatlantic Topographies’, Journal of British Studies, 51:1 (2012), p. 174.

- Perry (2012), p. 175.

- Perry (2012), p. 175.

- Perry (2012), p. 175.

- Michael Keith, Race, Riots and Policing: Lore and Disorder in a Multi-racist Society (London: UCL Press, 1993), p. 33.

- Anon., ‘Who Killed Aseta Simms?’, The Radical History of Hackney (2016) <https://hackneyhistory.wordpress.com/2016/09/11/who-killed-aseta-simms-1972/> [accessed 13.05.2021].

- Anon., ‘Who Killed Michael Ferreira?’, Bishopsgate Institute Reference Library: Copy No. 34/12(London: publisher unknown, 1979), p. 15.

- ‘Who Killed Michael Ferreira?’ (1979), pp. 11-12; Schling (2017), p. 46.

- Alan Denney, ‘Michael Ferreira’s Funeral 1979’, flickr.com <https://www.flickr.com/photos/alandenney/2440025741/in/album-72157604662835853/> [accessed 13.05.2021].

- Alan Denney, Personal Communication with Author (08.05.2021).

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Anon., ‘Who Killed Michael Ferreira?’, Bishopsgate Institute Reference Library: Copy No. 34/12(London: publisher unknown, 1979).

- ‘Who Killed Michael Ferreira?’, pp. 4-6.

- ‘Who Killed Michael Ferreira?’, p. 8.

- ‘Who Killed Michael Ferreira?’, pp. 8-11.

- ‘Who Killed Michael Ferreira?’, p. 16.

- Keith (1993), p. 221 (emphasis original)

- Anon., photographs of ‘Roach Family Support Committee March’, Rio Tape/Slide Newsreel Group (1983).

- RFSC, ‘Bulletin of the Roach Family Support Committee’, No. 3 (London: RFSC, 1983), p. 4 <https://hackneyhistory.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/roach_bulletin_3.pdf> [accessed 13.05.2021].

- Eden, ‘“They Hate Us, We Hate Them”’ (2014).

- Eden (2014).

- Bartholomew, (2018).

- Bartholomew, (2018).

Reblogged this on The Radical History of Hackney and commented:

A great blog post by Tom Ramsden that uses and expands on material from this site and other interesting sources.

LikeLike