In the month of October we will be marking Black History Month by sharing a series of short essays written by four recent graduates of the History Department at the University of Manchester. These students were part of Kerry Pimblott’s third year seminar on the Black Freedom Movement and were tasked with putting their new historical skills to work by performing original research on the transnational links between movements for racial justice in the US and UK. We would like to extend our thanks to the many archivists and librarians who assisted the students indeveloping these important profiles in Black British History.

Our third blog post on the British Black Panther Movement is from Estelle White, a recent graduate of the University of Manchester History Department.

“Black is Beautiful”

A revolutionary movement emerged within black communities during the 1960s and 1970s. This movement is known as the Black Power Movement, which placed an emphasis on “racial pride, economic empowerment, and the creation of political and cultural institutions”. [1] According to historian Peniel E. Joseph, Black Power activists “argued for a fundamental alteration of society,” not just societal reform. [2]

While the roots of Black Power can be traced back to 1954, in Richard Wright’s non-fiction book: Black Power, the concept of Black Power wasn’t mainstream until 1966, when Stokely Carmichael, a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), had a rallying cry of “we want Black Power now,” during the March Against Fear in Mississippi.

The Black Panther Party (BPP), was the main group of activists associated with Black Power. Originally named the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence, it was established in 1966 by two young Black students, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. The party was organised to simultaneously channel increasing frustrations towards the police and create “new programs to serve the city’s poor”. [3]

Rooted in Black Nationalism, the Panthers established their own schools where they taught Black history, held free breakfast clubs to feed children, encouraged the creation and support of Black businesses and also taught self-defence classes, as they strongly believed Black people had a right to defend themselves against discriminatory violence.

Transnational Struggles

While the Black Power Movement (BPM) is famously known for being a part of American history, it is also has a place in UK Black history too, although it has been widely unspoken of in historical literature. There are few famous examples of Britain’s attempts to obtain Black freedom, including the copycat Bristol Bus Boycott in 1963, adapted from Martin Luther King’s Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, and the “drink-ins” which briefly occurred in British pubs, imitating the student “sit-ins,” which took place in the US in the 1960s. Nevertheless, historians have been working to bring the stories of UK Black Freedom struggles from the shadows. Groups such as the Remembering Olive Collective and the Do You Remember Olive Morris? Project, have recently brought attention to the movement in the UK, exposing key leaders, who had been hidden in forgotten memories. These groups not only shed new light on the achievements of the BPM in the UK, but they also brought new attention to the Black women who were involved in the movement.

Throughout the Civil Rights Movement from Marcus Garvey and A. Philip Randolph, to Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, and to Stokely Carmichael and Fred Hampton, men have dominated the top roles when leading Black people to freedom. Meanwhile, the efforts of Black women have often been overlooked. However, there were many Black women in both the US and the UK who had integral roles in leading the fight for freedom. When focussing on the UK BPM, Olive Morris, Althea Jones-Lecointe and Beverly Bryan are just a few of the women who made big impacts. But before we delve into each of their heroic stories, and discover how these Black women led the UK BPM, we must first look at how the US Black Panther Party (BPP), acted as a blueprint for the Panthers in the UK.

Hostility breeds revolution

The UK BPM “appropriated the US Panthers’ revolutionary aesthetic”. [4] The BPP’s Ten Point Program: a list of demands including a call for an “immediate end to police brutality and murder of Black people,” was supported by the UK Panthers, who had the same aims. [5] Both branches of the party, embraced an infamous and unmistakeable uniform of afro hair, “black leather jackets […] and black berets.” [6] The UK also centralised a focus on self-determination, producing schools to teach Black history, creating and supporting Black businesses, fundraising for their communities and teaching self-defence classes at Oval House in Lambeth, to prepare them for “encounters with the state”. [7] The UK Black Panthers did not engage “in armed resistance to the police like their namesakes,” in the US, but they did have issues with the policing in their communities, as it was fuelled by racist biases. [8] While the UK Panthers did not carry guns, due to the stricter gun laws in the UK, some members did carry knives as a means of protection.

The Black population in Britain tripled between 1961 and 1964, from “300,000 to 1 million,” which caused an increase in racial and class tensions. [9] It was from this hostile environment that the UK BPM arose. While there were no Jim Crow laws in the UK, de facto discrimination was still widely practiced in society. Racism in the UK was “more subtle […] but no less effective,” than it was in the US. [10] Signs stating: ‘no Blacks, no dogs, no Irish” were commonly found outside of public spaces, such as hotels, restaurants and pubs. The UK also had “sus laws”, and these were protested against by the Black Panthers for being unjust and fuelled by racial prejudice. The BPP also protested against the police forcefully infiltrating “places where Black people were frequent,” such as the aggressive policing used at the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill. [11]

The Movement must stay masculine

When Obi B. Egbuna formed the UK BPP in 1968, he insisted the movement would only be successful if it remained masculine. However, Black women were tired of being “undermined and overshadowed,” and they worked to abolish the fictitious belief that they could not be successful leaders of the Black revolution. [12] Female members of the Black Panthers knew they not only had to fight for liberation from racism, but also from sexism. There were a number of female activists involved in the UK BPP who made an impact on the success of the movement. Olive Morris co-founded the Brixton Black Women’s Group in 1974, Althea Jones-Lecointe led the BPP following Egbuna’s arrest in 1970, and Beverly Bryan opened and taught at Black Panther led Saturday schools, teaching children about the true Black history. Black women’s groups in Britain “challenged the masculine chauvinism of Black Power,” [13] and women were often found on the frontlines defending “Britain’s Black communities against hate and terrorism”. [14]

“The key to larger memories of a time that has not been well documented”

One Black revolutionary woman was Olive Morris. Emigrating from Jamaica to South London with her father and brothers at 9 years old, it was only a few years before Olive became heavily involved in the UK BPP. Joining the party at 16, she quickly became someone who was recognised for challenging the men who patronised her and refused to give up on the fight for freedom. Olive’s eagerness to volunteer, and undeniable spirit towards the movement are well remembered by her friends and those who worked with her. [15]

At 17 years old, she was involved in violent conflict with the police. She was arrested and viciously beaten by the police, before being forced her to prove she was “really a woman,” by stripping down to her underwear in front of them. [16] Olive was photographed leaving King’s College Hospital after this attack, and has handwritten a caption on the back reading: “after the police had beaten me up”.

Olive was known for having found a way to fight for justice, and also make change. She impacted the BPM as a community activist not only in London, but also in Manchester. She knew oppression was an intersectional issue, identifying racism could not be confronted without also acknowledging how it intersects with sexism, class oppression and colonialism. Olive co-founded two Black women’s groups, the Brixton Black Women’s Group (BBWG) and the Manchester Black Women’s Co-operative (MBWC). People travelled from all over to be involved in these groups, as they tackled issued all Black women could relate with. [17]

The BBWG addressed specific issues which marginalised Black women and offered them advice and support, whilst also campaigning for change. The MBWC had a more focused approach on combatting inequality in white-collar employment in Manchester and offered professional training for Black women who had ambitions to work in offices. [18]

Olive spent 11 years tirelessly fighting in the UK BPM, combatting the racism and sexism Black women faced, in attempts to liberate them. Her life was tragically cut short when she suddenly died at 27 from Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Her friends believe she would still be an activist today if she were alive. Despite her premature departure from the BPM, her legacy as a revolutionary Black woman still remains, with the magnitude of her efforts being even more impressive due to the limited time she had to make an impact.

Most Powerful Black Woman of Her Time

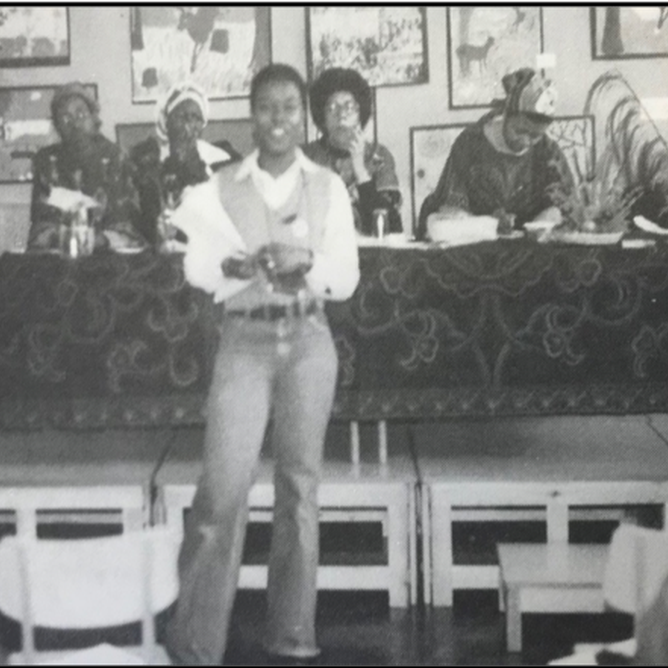

Althea Jones-Lecointe was the brains behind the leadership of the BPP following Egbuna’s arrest in 1970. Despite being “one of the most powerful Black women,” in the UK at the time, she is noticeable absent from a lot of the limited historical literature on the UK BPM. [19] Her evident absence is perhaps due to the fact she tried to remain anonymous when working with the Panthers. She came from a revolutionary Trinidadian family that was deeply involved in radical activism surrounding Black Freedom struggles. Her mother was a member of the Women’s League of Trinidad’s Independence Party, and from a young age Althea accompanied her mother on marches, knocking on doors and campaigning. It was during these times that the fire of activism was lit in Althea, and what pushed her to lead the UK BPP through great successes.

Following the racism she experienced when studying at University College London, Althea got involved in student anti-racist politics. She was involved in a student sit-in at her student union, which was supported by the BPP which initiated her involvement with the organisation. Althea had “rigid discipline and revolutionary fervour,” that many knew could rival that of any man. [20]

During her leadership within the BPP, Althea built formal structures to protect Black woman and girls from sexism and violence. As leader of the BPP, she ensured any men who were suspected of abusing or exploiting women were summoned before the central core, and if found guilty were punished. Also under her leadership of the Panthers, there were 148 catalogued incidents of police harassment and violence, with 0 victims ending up in prison or hospitals. The UK BPP held 147 demonstrations against police brutality and institutional racism and 77 cultural events were held. [21]

One of the most significant incidents of Altheas career as leader of the BPP, was the case of the Mangrove Nine. Black communities in London were tired of the police forcefully infiltrating ‘Black spaces’, one of the spaces that was unfairly targeted by police was the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill. In 1970 a group of 150 Black people met Althea outside the restaurant and marched from the restaurant to the local police station in protest of the unjust raiding of the restaurant. With “truncheons drawn and bricks raised,” the march turned violent and chaos erupted. Althea attempted to help a woman who had been struck amidst the violence and was bleeding from her face, but was arrested and carried away. Eight other arrests were made, and the group arrested would become known as the Mangrove Nine. The trial was Britain’s most influential Black Power trial.

The Mangrove Nine were accused of inciting a riot, and lasted for ten weeks. Althea represented herself in court and successfully exposed the racism of police constables who was unable to identify a Black suspects or tell Black people apart. This trial resulted in the Mangrove Nine being acquitted of their charges and was the first to acknowledge racial hatred from within the London police racism. [22]

The success of this influential trial is largely due to Althea and Darcus Howe’s decision to defend themselves during the trial and their demand for 63 jurors who they perceived as unfit to be dismissed form the trial. Althea’s impact on the BPM is irrefutable. Another revolutionary Black woman making big advances within the BPM.

Beverly Bryan – the Saturday Schools for Our Black History

Similarly to the US BPP, the Panthers in the UK also believed it was essential for Black people to be educated about their history and their truth in order for them to be able to liberate themselves. Beverly Bryan was one of the female activists who got involved in the educational side of the BPP.

Before becoming involved in the BPP, Beverly had been involved in Black organisations before but when she moved to London she felt she needed to be involved in a more radical organisation. She had been involved in Black organisations before however she felt she wasn’t doing enough, and so joined the BPP in 1970. [23] She worked alongside Olive in setting up the BBWG, and mainly tackled the issue of education in Black communities. As Beverly was a teacher at a school in Brixton already, she used her knowledge and skills to help set up and teach at Saturday schools, specifically designed by the BPP to educate Black children. Beverly believed a curriculum to defend Black people against racism and teach then about their blackness and their truth needed to be created. [24]

For the Panthers, their Saturday schools were more than just educating Black people on their true history. It was also about teaching Black children to be proud of their blackness, reminding them that “Black is beautiful”, and they’re not second class citizens. Beverly’s work at the Saturday schools and with the BBWG helped the Panthers do this.

Where Would We Be Without the Women?

Ultimately it is clear to see, despite what literature suggests, there were indeed powerful women who achieved successes in the BPM in the UK. From establishing Women’s groups, to causing the state to realise the police system has a institutional racist bias and to establishing schools designed to educate Black children on who they are and where they come from. The women of the BPP were integral to the progress of the BPM in the UK. Without their input who knows how far the BPM would have progressed in the UK. The BPP could have dissolved following Egbuna’s arrest if Althea had not taken over the leadership and led the party to further victories. Without Olive Morris, it could be argued the BPM may not have spread across the UK as it did, or have had such a popular youth following in London. And without the Black Panther Saturday schools, and the teachers like Beverly Bryan, a generations of Black children may have never had proper teaching about their history, and may never have been so largely encouraged to embrace their blackness in UK society.

Notes:

[1] National Archives, ‘Black Power’, 11 December 2018, https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power, [accessed 26th November 2019].

[2] Anne-Marie Angelo, ‘The Black Panthers in London, 1967-1972: A Diasporic Struggle Navigates the Black Atlantic’, Radical History Review, 103, (2009), PP. 350.

[3] Henry Hampton and Steve Fayer, Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights movement from the 1950s through the 1980s, (New York: Banham, 1991), pp. 350.

[4] Anne-Marie Angelo, ‘The Black Panthers in London’, pp. 18.

[5] The Black Panthers: Ten Point Program, 1996.

[6] Henry Hampton and Steve Fayer, Voices of Freedom, pp. 351.

[7] Anne-Marie Angelo, ‘The Black Panthers in London’, pp. 26.

[8] Rob Waters, ‘Becoming Black in the Era of Civil Rights and Black Power,’ in Thinking Black: Britain 1964-1985, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019) pp. 40.

[9] Anne-Marie Angelo, ‘The Black Panthers in London’, pp.21.

[10] Tanisha Ford, ‘Finding Olive Morris in the Archive’, pp. 12.

[11] Anne-Marie Angelo, ‘The Black Panthers in London’, pp.24.

[12] W. Chris Johnson, ‘Guerilla Ganja Gun Girls: Policing Black Revolutionaries from Notting Hill to Laventille’, Gender & History, 26:2, (November 2014), pp. 662.

[13] Rob Waters, ‘Becoming Black in the Era of Civil Rights and Black Power,’ pp. 49.

[14] W. Chris Johnson, ‘Guerilla Ganja Gun Girls’, pp. 667

[15] Do You Remember Olive Morris? Oral history Project, interview with Hurlington Armstrong, 2009, London, Lambeth Archives, Olive Morris Collection, IV/297/2/17/1-5. Used with permission and thanks.

[16] Tanisha Ford, ‘Finding Olive Morris in the Archive’, pp. 12.

[17] Do You Remember Olive Morris? Oral history Project, interview with Judith Lockhart, 2009, London, Lambeth Archives, Olive Morris Collection, IV/297/2/6/4. Used with permission and thanks.

[18] Ana Colin, Tanisha Ford et. al (eds.), Do You Remember Olive Morris? (London: Aldgate Press, 2009), pp.42.

[19] Rob Waters, ‘Becoming Black in the Era of Civil Rights and Black Power’, pp. 40.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] W. Chris Johnson, ‘Guerilla Ganja Gun Girls’, pp. 673.

[23] Heather Agyepong, ‘The Forgotten Story of the Women Behind the British Black Panthers’, 10th March 2016, https://graziadaily.co.uk/life/opinion/forgotten-story-women-behind-british-black-panthers/ [accessed 2nd December 2019].

[24] Simon Hollis and Kehinde Andrews, ‘The British Black Panthers’, BBC Radio 4 Podcast, 3rd August 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m0007b0y, [accessed 29th November 2019].